Monday, July 24, 2006

Cuban foreign aid...to the U.S.

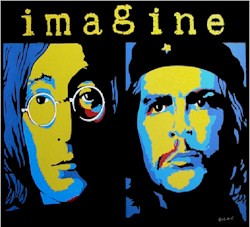

I've written before about the Americans receiving free medical school training in Cuba. Yesterday's Washington Post has a fascinating (and lengthy) article profiling the two of them pictured here. I'll leave the interesting details of their lives to the article, for those who want to read it, but I do want to pick out a few sections which have some interesting general observations for this post.

I've written before about the Americans receiving free medical school training in Cuba. Yesterday's Washington Post has a fascinating (and lengthy) article profiling the two of them pictured here. I'll leave the interesting details of their lives to the article, for those who want to read it, but I do want to pick out a few sections which have some interesting general observations for this post.Start with this:

Cuban doctors place a premium on basic skills -- interpreting breath sounds from a stethoscope, for instance -- that have been deemphasized in the high-tech world of U.S. medicine. Not long ago during rounds, Melissa's professor exploded at her when he asked for a diagnosis of a patient, and she replied that the lab results weren't back yet.Then this:

"Are you planning to become a doctor or a lab analyst?" he growled. "Tell me what you heard and felt and saw."

Most U.S. medical students are both white and well-off. Only 6 percent of students entering medical school in 2000 were from families earning less than $50,000 a year; only 6 percent of doctors in the United States are black, Hispanic or Native American.Things used to be a bit different before the era the media likes to describe as the "Reagan revolution." Some revolution:

The United States once had a successful program similar to the one being offered by Cuba: The National Health Service Corps Scholarship Program offered thousands of Americans free tuition and expenses in return for later practicing in areas that needed more doctors. Minorities relied heavily on the program: In 1980, one of every four black medical students had a corps scholarship.And why are these scholarships (the lack of them in the U.S., and the generous provision of them by Cuba) so critical? Here's why:

But the Reagan administration began slashing the program each budget year. In 1981, the corps offered 6,159 scholarships. In 1982, the number was cut to 2,449. Last year, the corps awarded 90 new scholarships.

At her high school in Houston, Melissa loaded up on as many science courses as possible. She won a full scholarship to Howard, where she graduated as a premed student with a 3.2 grade-point average. She'd saved $1,600 from a part-time job at Howard to pay for the Medical College Admission Test and a prep course. The prep course turned out to be a study in disillusionment.Note that none of that even included the cost of medical school itself, just the cost of getting in to medical school.

"They recommended we apply to no less than 14 schools, and each school application costs at least $200. I'd just spent two years saving the $1,600, and now I need another $2,800 just to apply to schools? Then, if you're lucky and a school calls you, you have to fly there and stay in a hotel. They even had the finite details about what to wear, and you'd have to buy a business suit, and everything was more money and more money and more money, and even then maybe you wouldn't get in."

One detail:

The walled compound was a naval base that Castro turned into a medical school to train students from all over Latin America.I believe in the Bible that's called "swords into plowshares."

And what kind of doctor will these two, and their classmates, become when they finish? The Cuban kind:

During summers with her grandmother in Alabama, she's volunteered at a free medical clinic, where she says there's been real appreciation for the skills she's learned in Cuba. "I've gotten to know a doctor in Birmingham who has worked all over the world. He worked in West Africa on disaster relief, and American doctors were, like, 'I don't have this, I don't have that,' but the Cuban doctors just went to work," she says.Update: For additional reading, today's online discussion of the article with the author and Melissa is here.

The doctor, Tom Ellison, a Birmingham cardiologist and epidemiologist, says Melissa has the makings of a great doctor. "On rides on our mobile clinic to an impoverished rural area outside Birmingham, I saw her dedication, her work ethic, her rapport with patients," Ellison says.